Indian Motorcycles celebrate their King of the Baggers championship by producing a limited-edition copy of their winning bike. This $92,299 (Rs 75.68 lakh) machine is an exact copy of the 2022 winning bike.

Story: Adam Child ‘Chad’

Photography: Jason Critchell

To commemorate winning the King of Baggers race series, Indian Motorcycles and S&S Cycle have done something extraordinary. They have produced a limited-edition run of 29 exclusive Challenger RR races bikes, exact copies of the beasts on which Tyler O’Hara won the 2022 Championship (and Jerry McWilliams won the dramatic Daytona race in the same year). Yes, you can buy this monster—but you will have to shell out $92,299 (Rs 75.68 lakh).

This is not a watered-down version of a race bike, all sharp edges sanded down for public consumption, but a ready-to-race replica. That means years of track development, completely new suspension, wheels, braking, and chassis, plus a big-bore 60-degree V-twin enhanced from 1,768 cubic centimetres to 1,834 cc.

And it is a phenomenal motorcycle: one that weighs some 281 kilograms yet is capable of speeds on the Daytona banking of over 290 km/h and is able to lap within a few seconds of the top runners in AMA Superbike. All this, despite being based on Indian’s Challenger, one of the most laid-back baggers on the planet complete with 6.5-inch speakers for blasting tunes at fellow tourers along Route 66. In fact, the transformation of 361 kg of prime American beef designed to run on a 19-inch front wheel and a 16-inch rear one into a crazy-fast track tool is beyond genius or comedy or reason. The result beyond compare.

The original MotoAmerica King of Baggers race that ran back in October 2020 was not meant to be too serious; converting laid-back American baggers into race bikes was meant as a fun idea and one-off spectacle. But the best-selling bikes in the United States of America are baggers, car parks are littered with them with sports bikes relatively thin on the ground these days, and that first race was a huge success, creating a social media storm as video emerged of a grid full of faired and bagged V-twin behemoths thundering into Turn One.

It was an obvious decision to run a full series the following season, since when the King of the Baggers race series has grown each year, gaining in popularity, attracting new sponsors as well as world-class riders and, perhaps most significantly, rekindled the historical battle between Indian Motorcycles and Harley-Davidson. It could be argued that bagger racing is one of the most exciting and interesting race series in the USA right now.

But converting a road-going bagger, which is essentially a big American V-twin cruiser with bags, into a race bike is a mammoth task, not only testing the teams’ skills and ingenuity but also the extent of their financial resources.

Indian Motorcycles Racing and S&S Cycle have decided to celebrate winning the King of Baggers Championship in 2022, their second on the trot in the hands of Tyler O’Hara, by producing this hand-built replica. Production is limited to just 29 units and, as mentioned earlier, it is priced at £90,000 (Rs 93.6 lakh).

Converting a road-going sports bike into a race bike is a hard task. BMW produce an excellent S 1000 RR, yet are still to achieve World Superbike success with it in 2023. Converting a laid-back American bagger into a race bike is monumentally difficult; into a race-winner more difficult still. The standard road bike, complete with that stereo, is so far removed from the needs of the racetrack, yet, incredibly, some of the road-going parts remain on the championship winning Challenger.

The race bike’s main frame is stock while the swing-arm benefits from added bracing. The race fairing is a copy of the road bike—the rules require the same dimensions and look as roadster—but headlights, music players, and road clutter can be removed. The gas tank—sorry, fuel-tank—is the same and despite the V-twin’s increase in power, the large radiator is also stock. The core of the engine remains stock, including the transmission and gear ratios.

Essentially, the largest problem the engineers face is getting the Challenger to handle and this means improving the brakes, suspension, tyre grip, and, of course, limited ground clearance—which is why the bike has been so dramatically lifted.

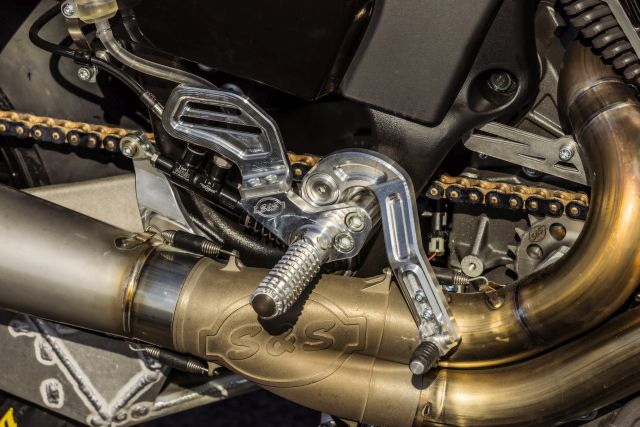

The 19-inch/16-inch wheel combination of the standard bike has been replaced by lightweight forged-aluminium 17-inch rims on Dunlop slick rubber. The front brakes are completely new and uprated to Brembo M4 calipers and 330-millimetre rotors—sorry, discs. Suspension is bespoke, produced by Öhlins, and fully adjustable. The bagger’s footboards are gone, replaced by S&S rear-sets and a quick-shifter kit. Then there are the trick parts, by S&S: billet adjustable triple clamps and clutch cover, chain drive conversion, and automatic chain tensioner.

The 60-degree V-twin also gets a significant overhaul, though power and torque figures remain a closely guarded secret (even Jeremy McWilliams would not reveal to me despite sharing a few beers). The standard 1,768-cc capacity is up to 1,834 cc; stroke remains the same at 96.5 mm but bore is up to a whopping 110 mm from 108 mm. There are CNC ported heads, S&S camshafts, a completely new air intake system, and a huge 78-mm throttle body to feed that huge motor. An S&S two-into-one race exhaust makes it sound like the end of the world. Meanwhile, the rev-limiter is set to a lowly 7,500 rpm because this motor is all about torque.

The minimum weight is set at 281 kg by the rules, which is relatively simple for Indian to achieve and why there is no carbon-fibre onboard, except the huge bags, and you will not find any titanium either. These are carbon to minimize the likely instability caused by hard luggage at 290 km/h. And while the racing Challenger remains a ludicrously heavy machine for the track, it is some 100 kg lighter than the bike it is based on.

The wheelbase is around the same as the standard bike’s, but rake and trail are steeper and shorter to help the brute turn. But the most dramatic change is in the seat height, which has leapt up from 672 mm to 889 mm, which is higher than BMW’s R 1250 GS (870 mm) and even KTM’s skyscraper 1290 Super Adventure (880 mm). This is one long, wide, heavy, and tall motorcycle, yet one that at some tracks is only three to four seconds slower than an AMA superbike and, at Daytona, attains more than 290 km/h. Truly, the Indian technicians and S&S Cycle team have worked magic.

I have been riding bikes on a professional basis for nearly 25 years but nothing prepared me for this. Like most, I have watched bagger racing on YouTube and knew the bike would be a beast; but in the flesh it is enormous and wildly intimidating too. To add to the sense of dread, it sounds like it wants to kill you even as it is being warmed up.

Problem number two: at just 172 centimetres I am on the short side and cannot get anywhere near touching the floor and need two technicians to hold the bike as I get on to it and to catch me when I come back down pit-lane. McWilliams reported that he once stopped for a practice start, did not plan accordingly, toppled over, and could not pick it back up.

Brilliant. So I am about to ride a monster of a race bike of unknown ferocity, that I need help to get on, that weighs as much as two Moto2 machines, and is number three of the 29 to be built… and worth $92,000 (Rs 75 lakh).

Once astride, with some help, it feels like a building. The tall hard race seat is met by bars that are very wide, while the bodywork’s acreage seems immense. My right leg sits just behind the huge air-filter and, as I take control of the bike from my helpers, the RR gets angrier with every deafening blip of the throttle.

I nudge up on the S&S race shift, give it some angry revs, let the clutch out as an Indian technician pushes me for the first few metres like a child taking their first ride without stabilizers, and this mountain on wheels trundles down pit-lane, exhaust reverberating against the Anglesey pit wall. Now it is just me, an empty track, and a very unusual race bike—like nothing I have ridden before.

Thankfully, Indian had laid on an FTR1200 to get me familiar with the Welsh track (basking in perfect conditions), so there were no excuses: it was time to unleash the beast. Jeremy McWilliams had advised me to use the torque—‘Don’t bother with first gear,’ he had said—so, I short-shifted into second, then third.

The drive is immense, the slightest touch of the throttle opening the floodgates to a wave of torque like no other race bike I have ridden. The RR revs out at 7,500 rpm, where most race bikes start making their power, and all my focus is on managing the V-twin’s mid-range muscle.

There is no time to dawdle; I am on scrubbed and pre-heated Dunlops and need to maintain their heat. However, I also have to remember there are no electronic rider aids like traction control—and the throttle is very direct.

Into Turn One for the first time and it is in with the clutch, for the quick-shifter only works on up-changes, and back to second for the long wide hairpin. The brakes are surprisingly strong considering the bike’s weight and the steering is not bad either. Already, I am riding the Challenger RR like a conventional race bike, hanging off the inside, but it is comical how tall it is, how far up my knee is from the track below. I make a mental note: plenty of grip and ground clearance, just try harder.

On the back straight, which is actually a long banana of a curve, and it is time to unleash the V-twin. I tap the smooth shifter into third, fourth, and even grab fifth. I am only tickling the throttle but acceleration is dramatic as one wave of torque after another shovels the bike forwards. I tuck in, as you would on a conventional race bike, but realise that with such a huge fairing, there is no need to do so.

Up to the second and third gear complex towards the end of the lap and again the steering and braking are direct and responsive in a way you simply would not expect on a 281-kilo wildebeest. I am trying to keep everything smooth and wide, use a tall gear to allow the bike to flow, not stop-start or use any of that modern, squaring-off nonsense. Rolling down through Anglesey’s “corkscrew”, I am amazed by the Indian’s deceptive lightness and fluidity. You would never guess this was a nearly 300-kg bike, not a chance.

As I hit the home straight, I know the Indian crew are watching, so it is time to put my head down. This time into the hairpin, it is back two gears but you have to be careful on down-changes as there is so much torque and, rather old-school, you have to use the clutch.

The huge Brembo stoppers are up for the job and this time as I roll the RR into the turn, my knee hits the Welsh racetrack for the first time. The seat is taller than BMW’s R 1250 GS’ but the grip developed by the Dunlop race rubber and the extra clearance engineered into the bike means there is plenty to come. I am hanging off mid-corner but nowhere near the limit of the bike. Elbow down, by the way, is not an option.

Out of Turn Three (taken in third gear), I open the throttle hard and the drive is off the scale. A force like no other. This bagger just wants to take off. And under such hard acceleration the rear goes vague and lets me know that this is not a thoroughbred race bike developed from a sports bike, but from a lazy, laid-back cruiser.

This happens every lap as I ask for all that torque to be laid to the ground and wonder if the RR’s combination of immense grip and torque is somehow overwhelming the chassis’ ability to harness all the energy it creates.

Once the power is laid down—and you have force running through the shock and chain—stability is not bad. But on the initial pick-up of the throttle, the rear can feel vague, either chassis flex, anti-squat or both.

I doubt I was ever at 100 per cent throttle during my ride on the Challenger RR, probably not even at 90 per cent in actual fact, and certainly did not witness the shift lights as there is simply no need to rev it hard. It is tricky to estimate just how much torque is being churned out as it is so different from any race bike, but there is no doubting it is quick under acceleration. Super quick.

However, it is not all about the engine. What the Indian technicians and riders have done in terms of handling is a minor miracle. The front end is stable with braking able to consistently slow 290 kilos, plus rider, from potentially 290 km/h. In fact, you can ride the front end like a 150-kilo race machine.

The last section of the lap is technical and taken in third gear, allowing the bike to flow (the fuelling and snap from the throttle is a little too snatchy in second gear) and a real test of the accuracy. The Indian performed admirably, holding a line, hitting its apexes perfectly while hiding its weight, and finding a natural flow.

Each lap it encouraged me to get more into the flow, albeit at my relatively low speed compared to McWilliams’. Get the chain tight, then dial in the torque. Brake later, then let go of the lever, and carry the corner speed with a lot of vertiginous lean angle. Then it is back on the throttle and time to be deafened again by the rudest of race exhaust systems.

On my way back to the pit-lane, I remember to plan my stop carefully. As I roll up to my Indian technician in neutral, I desperately try to get one secure foot down. Yes, my lack of height is a little embarrassing but I am just pleased to have the bike back in one piece.

The Indian Challenger RR is not as difficult to ride as I initially expected, not as intimidating as it looks and sounds, but does require skill and a different style of riding—way above my level. I can see why some riders click with bagger racing and some do not. I rode in perfect conditions and alone. God knows what it must be like on a tricky and fast track, in the wet, elbow to elbow with others!

I obviously wanted more laps and it would be great to test the bike again at a faster-flowing track like Donington Park or Mugello, but I did get a real flavour of what this bike is about and what it must be like to race a bagger. Just to dance with the devil, poke the tiger in the eye, and get away with it was an experience.

Converting a road-going sports bike into a race bike is an uphill task but converting a bagger into a race bike is astronomical; it is like climbing Mount Everest in flip-flops. They have made the Indian Challenger handle and go around a racetrack in a time not a million miles away from an AMA superbike. The transformation is incredible, arguably one of the toughest and greatest in two-wheeled racing today. Hats off to the Indian Motorcycles Racing team.

Numbers are limited, but if you want one, run to your local Indian dealer now…

Specifications

Indian Challenger RR

Price: From $92,299 (Rs 75.68 lakh)

Capacity: 1,834 cc

Bore x Stroke: 110 mm x 96.5 mm

Engine: Liquid-cooled, 60° V-twin,

Valvetrain: DOHC, eight valves

Power: NA

Torque: NA

Transmission: Six-speed, chain final drive, quick-shifter

Tank capacity: 22.7 litres

Rider aids: None

Frame: Stock

Front suspension: Öhlins FGR250 inverted forks, 43 mm, 130-mm travel, fully adjustable

Rear suspension: Öhlins monoshock, fully adjustable

Front brake: Twin 330-mm discs, Brembo M4 four-piston radial caliper

Rear brake: Single 300-mm disc, two-piston caliper

Front wheel/tyre: 17-inch / 120/70-17 Dunlop slicks

Rear wheel/tyre: 17-inch / 200/60-17 Dunlop slicks

Dimensions (L x W x H): Not available

Wheelbase: 1,670 mm

Seat height: 889 mm

Weight: 281 kg

Warranty: Not available

Website: www.indianmotorcycles.co.uk

Leave a Reply